|

|

home page back to events page

Raffertys Heaven can wait 24-hour Yacht Race by Helen Hopcroft 'To have cancer is to sail into the darkness. But it is for the weary sailor that the sun will rise in the morning'

Mannering Park Yacht Club on Lake Macquarie recently hosted a 24 hour yacht race to raise money for the NSW Cancer Council. The race was a success with over $20,000 raised for the Cancer Council. Seventy three boats participated in the weekend sailing, with 30 yachts racing in the 24 hour event. The winner of the 24 hour event was an Adams 10 called 'Brigitta', skippered by Phillip Yeomans. Peter Sorenson on his Bethwaite 8 yacht 'Vivace' was the fastest boat over a one lap course.

What is really interesting about this story is why a small, suburban sailing club decided to host a high profile race purely to fundraise for NSW Cancer Council.

Mannering Park Yacht Club was established in 1968 by workers from the nearby mines and power station. The first races involved a motley collection of VJ's, sabots, skiffs and catamarans. In the words of the current commodore, the races were open to 'anything that could float'. Nowadays the club holds a popular twilight sailing series on Wednesdays, and yacht and catamaran racing on Saturdays. They are proud of the fact that they have the largest 14' catamaran fleet in NSW.

The club is located on the shores of the western side of Lake Macquarie. It's right in the middle of the small suburb of Mannering Park. The club building is a square brick shed. Facilities are limited; there is a tiny kitchenette, a couple of toilets, and a few plastic tables and chairs. It's not the sort of place that you think of when you hear the phrase 'yacht club'. It is unassuming, friendly and slightly down at heel. It retains its working class roots; many of the club members work within the construction and building industry.

The club commodore is retired sailor Mike Lewicki. The Lewicki family is the lifeblood of the club. Like many community organisations, it only functions because of the energetic input of a few dedicated volunteers and the endless whining of others. Every weekend Mike and his wife Anne, Darcy Wilson and Ken Douglas, are down at the club making sure that the day's racing goes smoothly. Anne brings in cakes and crackers for people to snack on. The sailors buy cheap beer from the bar and choke down charred sausage sandwiches. They stand in front of the lovely view and talk about sailing. It's a genuinely nice day out.

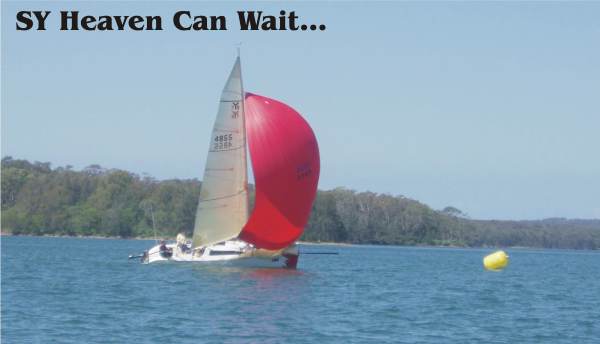

About three years ago Shaun Lewicki was diagnosed with cancer. He was thirty five. As for many people, this changed his life completely. By the time he had started to feel better his yacht, 'Heaven can wait' had been out of the water for four years.

The experience of battling cancer gave Shaun the idea for holding a yacht race to fundraise for the Cancer Council. He was lying in his hospital bed one day and counting the chips of paint that had flaked off the ceiling over his bed. He suddenly thought that the paint chips looked like a race course; if you kept the first chip to starboard, you could reach across to the second, it would be a spinnaker run down to the third etc…The 'Heaven can wait- 24 hour yacht race' was born.

The idea of the 24 hour race was to 'celebrate survivors and to remember those lost along the way.' Sponsorship was obtained from Rafferty's resort and a number of local and national businesses. These included Navman Marine Electronics, Ensign Mines and RFD Australia. The small Lake Macquarie yacht clubs of Wangi Wangi and Toronto supported the event. Rob Kothe publicised the event on his Sail World website, as did Prime TV and a number of local newspapers. Sailing Anarchy became involved in the event early on and did a tremendous amount to ensure that the event happened and was a success. The range of people and businesses that were prepared to put time and money into a new event was surprising.

The race took place on a blustery long weekend in October. It coincided with school holidays and the rugby league grand final. The wind was mainly southerly and gusted up to approximately 30 knots. Lighted buoys were put out to mark the night course. The race started at 1pm and finished the same time the next day. There were two divisions which started five minutes apart. Each lap was approx 31 nautical miles. 'Vivace' completed the fastest lap in three hours and twenty five minutes. A small fleet of trailer sailors also took part in the shorter race which was called the 'One lap dash'.

Sailors came from far and wide to participate. One crew drove down from Queensland the night before. There was another crew that flew in from the Northern Territory. Blake Middleton, a race official from the USA, flew over for the event. He was also a cancer sufferer. He found out about the race on the internet and was determined to attend. He said that it was 'the only regatta I have heard of conducted for the right reasons.'

The range of boats that raced was equally wide. There was everything from the fastest sports boats in Australia to a little Careel 18. A particularly fast vessel, from Sydney's Middle Harbour Yacht Club, was popularly considered to have been travelling at speeds of up to about 20 knots. A friend told me he watched it sail past and was so impressed that he forgot to breath. One unlucky vessel, 'Stealthy', broke it's rudder in the early stages of the race and had to pull out.

Race fees were a $50 donation per crew member for the yachts and $50 per boat for the trailer sailors. 10% of the races fees went to the volunteer Coastal Patrol and the rest went to the Cancer Council. Rafferty's resort, a luxurious waterfront restaurant and hotel on the east side of Lake Macquarie, made a very generous donation. There were trophies for the winning boats and Navman supplied some of their latest gear as prizes.

The club kitchen was busier than it had ever been with an army of volunteer cooks preparing meals for the sailors. The kitchen was run by a tough, good natured nurse called Sharon and a former publican called Jenny. The bar was also extremely busy. A great time was had by all participants. People stayed around drinking and talking long after the race had finished.

For the Lewicki's, the race was the culmination of months of hard work and a personal celebration of Shaun's recovery. They did a tremendous amount of work organising the event and running the race. Mike, who is in his 60's, said that after the race was over he and his wife 'could hardly stand up.' As such a small club, they had limited experience of organising an event of this size. They both say that they learned an enormous amount from the experience.

|

|

The participants in the 24 hour event reportedly felt a real sense of achievement and pride. Most of them finished the race feeling tired but happy. The idea of a 24 hour race was intended to link to the idea of experiencing illness. Sailing a boat for 24 hours on Lake Macquarie can be hard work. It may be frustrating, difficult and repetitive. But completing the course also gives a sense of euphoria and accomplishment. 'Heaven can wait' is a special race.

Shaun was also exhausted but exhilarated by the success of the event. He raced 'Heaven can wait' and came in fifth on handicap. It was the first time he had sailed his own boat in years. Early on Sunday morning the wind died off and the lake was absolutely still. His boat was stranded on the water near the small town of Toronto. He said that it was a frustrating experience to be floating there, unable to move. He started thinking about the many nights his wife Dianne sat waiting by his hospital bed while he was unable to move or talk. His crew became steadily more impatient as they waited for the wind to pick up. But he realised what an enormous thing it was to 'still be there in the morning'.

The club has decided to hold the race again next year. Visiting cruisers are welcome to participate. For more information email theheavencanwait24@bigpond.com or phone 02 4358 2495.