|

“Losing the “Cannon Bay”

continued...

“Cannon Bay” eventually sat like

a rock as the wind, easing slightly, veered into the south-west

then kept going to the north-west. I sat exhausted under the

lee of the wheelhouse waiting for dawn where I realised I was

not alone. Also enjoying the lee were a number of birds whose

normal timidity was abandoned in favour of security. Nothing

would convince them to fly off into the wind, not even my gentle

stroking of their saturated feathers. Cyclones are great levellers;

everyone becomes humbled.

Dawn exposed a rubbish tip of debris strewn far and wide, with

many buildings shattered beyond, dislodged off their foundations

or minus their roofs. Trees along the distant mountain ridge

were shorn off every vestige of foliage, looking for the world

like giant fish skeletons. And the Island's others vessel, the

15 metre passenger launch “Kiru” had broken free from

her mooring and was later found smashed ashore in North East

Bay.

|

|

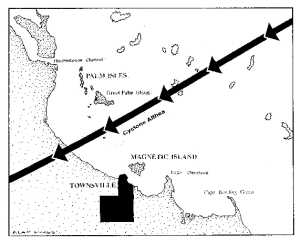

CYCLONE

ALTHEA DETAILS

Cyclone Althea rated as

one of Queensland's most destructive storms, not because she

was the strongest, but because her most destructive southern

semi-circle passed over a densely populated area (Townsville

then had 71,000 citizens). Her maximum gust was recorded at 109

knots (196 kilometres per hour) at Townsville Airport on 24th

December, 1971. It was generally believed that gusts much higher

than this occurred, especially near Cape Palleranda and on Magnetic

Island.

Her lowest central pressure

was 952 hPa. This compares with Ada's 962 hPa in the Whitsunday's,

January 1970 and, at the other extreme, the great Bathurst Bay

cyclone of 1899 whose low is a record to this day at 914 hPa!

Perhaps the most permanent

effect Althea had on Townsville was cultural, her massive destruction

attracting hundreds of southern workers to the area. Before Althea,

carpenters were paid around $2.00 per hour. After Althea, rates

went up to $10 per hour. Before Althea, a house in Railway Estate

could be bought for $4000. After Althea, just a block of land

fetched more than twice that price. Townsville lost its innocence

just as Darwin would three years later when cyclone Tracey did

her thing. |

Compared to Townsville, the Palm Isles

were lucky, having copped only the northern semicircle of Althea.

The southern half, the most destructive half, turned the city

of 71,000 people into a disaster area. Christmas Day was a dismal

affair of preliminary clean-ups, attempts to save food in the

absence of power, and for at least ten percent of homeowners,

a search for accommodation.

Ross Creek became the graveyard

of many vessels, some of which piled up on the slipway near the

Motor Boat Club, whilst others were stranded in city parks. Dozens

of glorious old fig trees along The Strand were uprooted and

a recently laid submarine pipeline to Magnetic Island virtually

disappeared.

|

|

Typical cyclone damage

about the place. |

|

Back on Palm Island, I used the

neap tides to patch “Cannon Bay” in the hope of a refloat

on the next springs. The Gardner's needed little more than a

wash-out and the hull seemed sound enough despite every seam

being started and many fastenings showing signs of failure. And

here, let me put to rest a persistent rumour that suggests she

was pulled off the bank and set adrift to become a navigational

hazard for weeks after. This is quite untrue. What happened is

this:

The assistant Director of Aboriginal and

Island Affairs (as the department was then called) flew up from

Brisbane a few days after the cyclone. We discussed the future

of “Cannon Bay” and I was categorically assured that

the Island would continue to manage its own cargo and passenger

deliveries using its own vessel. To this end, I was requested

to get the vessel into Townsville, book her onto Matt Taylor's

slipway and have her fully restored.

|

|

The Palms survive.......... |

My crew and I limped her into Townsville

as soon as she floated off on the next spring tide. Pumping all

the way, we were met at a public jetty (near the Motor Boat Club)

by the local fire brigade whose truck pumped her dry and promised

to be on call should we experienced trouble keeping her afloat.

The crew went home and I lived aboard for no other reason than

to keep her pumped out. When it became too much, the fire brigade's

offer was taken up on a number of occasions.

Weeks passed alongside that jetty waiting

for vacancy on the slip. It had to clear the wreckage off its

slipways and then rebuild its own infrastructure.

I spent my time pumping, sleeping and because

there was nothing else happening, boredom set in. This led to

a decision that I would quit the job as soon as the “Cannon

Bay” was in safe hands.

Such was the pressure on boat repair services

at the time, “Cannon Bay” was still unfinished towards

April, at which time I resigned. With a private barge contractor

supplying the Island and every indication that the department

would change its policy from one of supportive engagement with

the Palm Island community to economic rationalisation, I presumed

this private arrangement would continue. And I was right. Despite

the money poured into “Cannon Bays” repairs, she was

pensioned off and abandoned.

Her remains lie in the very same

cyclone creek on Palm Island that I hoped to enter after unloading

those Christmas supplies so long ago. As to how she became a

navigational hazard so soon after her restoration, I cannot say

but obviously someone managed to shove her into the creek. Perhaps

that hazard was not her at all, but another victim of cyclone

Althea.

|

|

The author........ |

|